Today is a day that’s been a long time coming. The Friend Grief blog is four years old, and

it’s been in need of upgrading for quite some time.

So as of today, I (also) have a new website:

VictoriaNoe.com.

This is a big step in a lot of ways. First of all,

it’s my name, not the subject of my books. It was important to take this step

because my writing has already begun to expand into other areas. That doesn’t

mean it was easy. Putting my name out front – rather than the books – has

intimidated me for a long time.

This fall will see the publication of the sixth and

final book in the Friend Grief

series: Friend Grief and Men: Defying Stereotypes. Next year they will be bundled into one book and released on audio. And

then…well, that announcement is coming soon, too.

I wanted to expand what I offer online to my

readers. So the new website includes a lot of new content:

Reviews

and book group discussion questions for each book

Resource

links specific to each book

A

complete list of my freelance articles and interviews

Sales links to the Friend Grief books as well as My Gutsy Story™ Anthology 2, which

includes a story of my own ("I'm Not Gutsy, But You Are")

I’m not one of those authors who’s intimidated by

speaking in public. So you’ll find a page devoted to public speaking, with presentations

I can bring to your event or class.

On April 29, I’ll send out my first weekly email

newsletter. I don’t want to fill up your in-box unnecessarily, so each one will be

short, sweet and timely. The first 100

people who sign up for it will receive a free pdf of the first chapter of Friend Grief in the Workplace: More Than an

Empty Cubicle, coming out in May.

I have the talented and patient folks at 1106 Design

to thank for their hard work on my new website. I hope you’ll check it out and

find a lot to like.

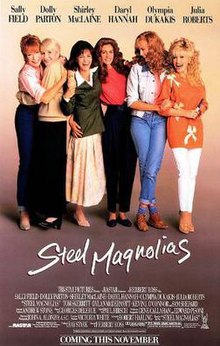

And have no fear: the Friend Grief blog will continue, with posts of my own, guests, book

and film reviews and more. So feel free to keep checking us out right here.

My thanks to you all who have followed me this far.

I’m not done yet.